Photo credit: Gerry Feehan

Abu Simbel, Egypt

It is exciting to look out the window of an airplane at the earth far below, noting where land meets water or observing the eroded remains of some ancient formation in the changing light. Alas, the grimy desert sand hadn’t been cleaned from the windows of our EgyptAir jet, so we couldn’t see a thing as we flew over Lake Nasser en route to Abu Simbel. I was hopeful that this lack of attention to detail would not extend to other minor maintenance items, such as ensuring the cabin was pressurized or the fuel tank full.

We had just spent a week on a dahabiya sailboat cruising the Nile River, and after disembarking at Aswan, were headed further south to see one of Egypt’s great monuments. There are a couple of ways to get to Abu Simbel from Aswan. You can ride a bus for 4 hours through the scorched Sahara Desert, or you can take a plane for the short 45-minute flight.

Opaque windows notwithstanding, I was glad we had chosen travel by air. Abu Simbel is spectacular, but there’s really not much to see except the monument itself and a small adjacent museum. So most tourists, us included, make the return trip in a day. And fortunately we had Sayed Mansour, an Egyptologist, on board. Sayed was there to explain all and clear our paned expressions.

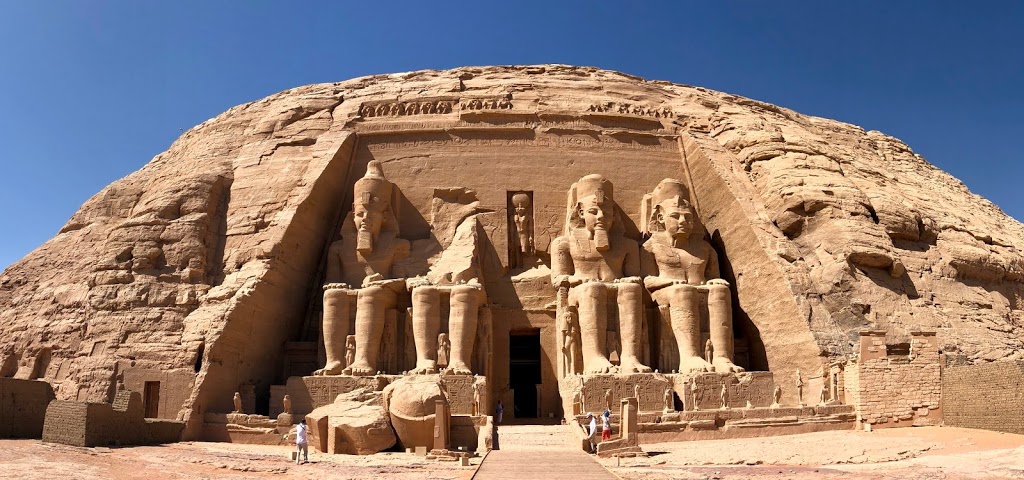

Although it was early November, the intense Nubian sun was almost directly overhead, so Sayed led us to a quiet, shady spot where he began our introduction to Egyptian history. Abu Simbel is a marvel of engineering – both modern and ancient.

The temples were constructed during the reign of Ramses II. Carved from solid rock in a sandstone cliff overlooking the mighty river, these massive twin temples stood sentinel at a menacing bend in the Nile – and served as an intimidating obstacle to would-be invaders – for over 3000 years. But eventually Abu Simbel fell into disuse and succumbed to the inevitable, unrelenting Sahara. The site was nearly swallowed by sand when it was “rediscovered” by European adventurers in the early 19thcentury. After years of excavation and restoration, the monuments resumed their original glory.

Then, in the 1960’s, Egyptian president Abdel Nasser decided to construct a new “High Dam” at Aswan. Doing so would create the largest man-made lake in the world, 5250 sq km of backed-up Nile River. This ambitious project would bring economic benefit to parched Egypt, control the unpredictable annual Nile flood and also supply hydroelectric power to a poor, under-developed country. With the dam, the lights would go on in most Egyptian villages for the first time. But there were also a couple of drawbacks, which were conveniently swept under the carpet of water by the government. The new reservoir would displace the local Nubian population whose forbearers had farmed the fertile banks of the Nile River for millennia. And many of Egypt’s greatest monuments and tombs would be forever submerged beneath the deep new basin – Abu Simbel included. But the government proceeded with the dam, monuments be damned.

Only after the water began to rise did an international team of archaeologists, scientists – and an army of labourers – begin the process of preserving these colossal wonders. In an urgent race against the rising tide, the temples of Abu Simbel were surgically sliced into gigantic pieces, transported up the bank to safety and reassembled. The process was remarkable, a feat of engineering genius. And today the twin edifices, honouring Ramses and his wife Nefertari, still remain, gigantic, imperious and intact. But instead of overlooking a daunting corner of the Nile, this UNESCO World Heritage site now stands guard over a vast shimmering lake.

Sayed led us into the courtyard from our shady refuge and pointed to the four giant Colossi that decorate the exterior façade of the main temple. These statues of Ramses were sculpted directly from Nile bedrock and sat stonily observing the river for 33 centuries. It was brutally hot under the direct sun. I was grateful for the new hat I had just acquired from a gullible street merchant. Poor fellow didn’t know what hit him. He started out demanding $40, but after a prolonged and brilliant negotiating session, I closed the deal for a trifling $36. It was difficult to hold back a grin as I sauntered away sporting my new fedora – although the thing did fall apart a couple of days later.

Sayed walked us toward the sacred heart of the shrine and lowered his voice. Like all Egyptians, Sayed’s native tongue is Arabic. But, oddly, his otherwise perfect English betrayed a slight cockney accent. (Sayed later disclosed that he had spent a couple of years working in an East London parts factory.) He showed us how the great hypostyle hall of the temple’s interior is supported by eight enormous pillars honouring Osiris, god of the underworld.

Sayed then left us to our devices. There were no other tourists. We had this incredible place to ourselves. In the dim light, we scampered amongst the sculptures and sarcophagi, wandering, hiding and giggling as we explored the interior and its side chambers. At the far end lay the “the holiest of holies” a room whose walls were adorned with ornate carvings honouring the great Pharaoh’s victories – and offering tribute to the gods that made Ramses’ triumphs possible.

Exterior photographs of Abu Simbel are permitted, but pictures from within the sanctuary are verboten – a rule strictly enforced by the vigilant temple guardians – unless you offer a little baksheesh… in which case you can snap away to your heart’s content. Palms suitably greased, the caretakers are happy to pose with you in front of a hidden hieroglyph or a forbidden frieze, the stern glare of Ramses looking down from above notwithstanding.

After our brief few hours at Abu Simbel, we hopped back on the plane. The panes weren’t any clearer but, acknowledging that there really wasn’t much to see in the Sahara – and that dirty airplane windows are not really a bona fide safety concern – I took time on the short flight to relax and bone up on Ramses the Great, whose mummified body awaited us at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Gerry

Travel Tips

Exodus Travel skilfully handled every detail of our Egypt adventure: exodustravels.com

Terry says

As usual a great and informative story. Thanks Gerry