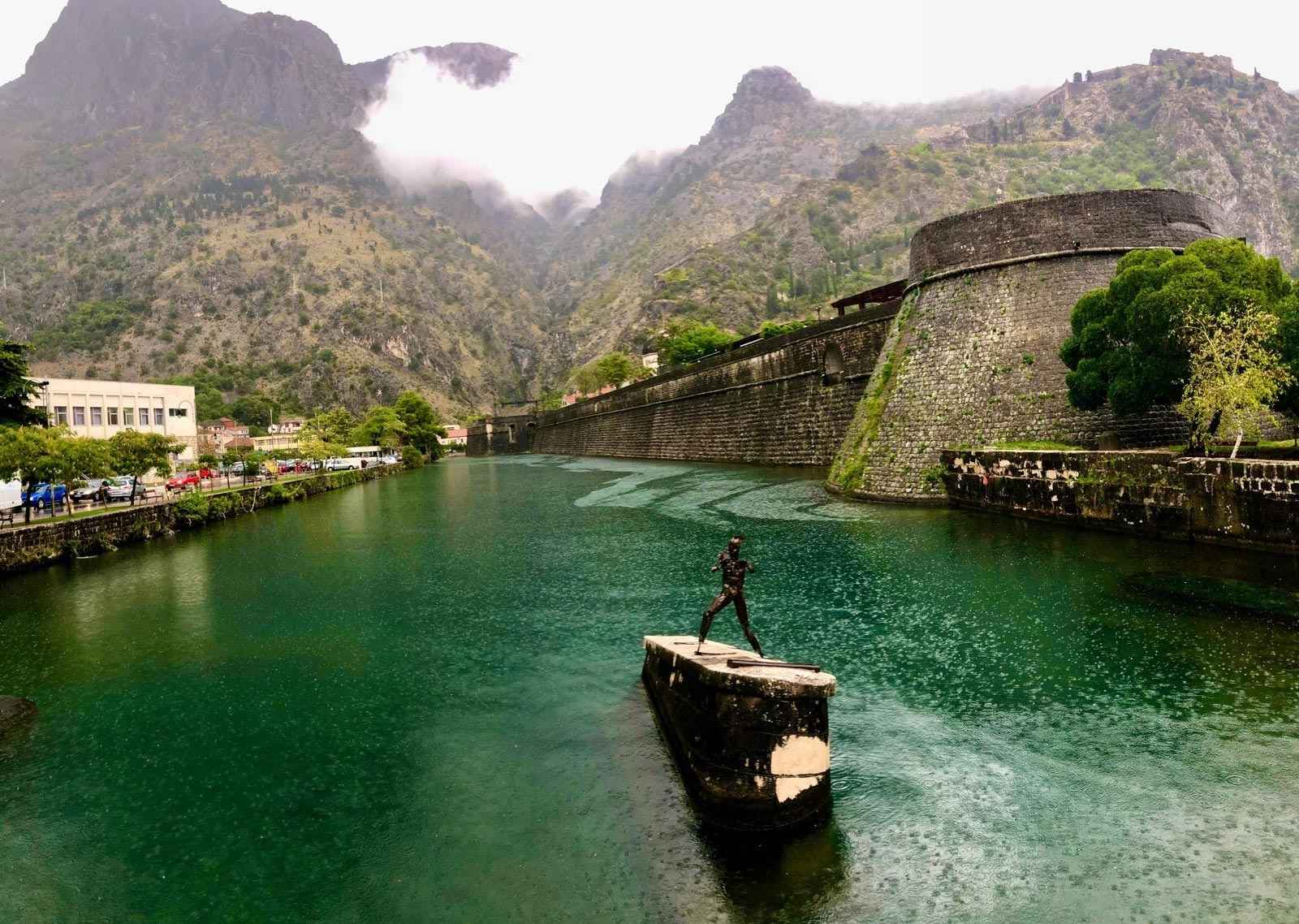

Photo credit: Gerry Feehan

A Rainy Day in Montenegro

Room 703, Valamar Hotel, Dubrovnik, Croatia.

I had a strange dream last night.

Well past midnight there came a quiet rap on the door. An apologetic bellboy pointed to a small man standing quietly in the hallway. The man sported a fine suit and monogrammed luggage. ‘I’m sorry,’ said the bellhop, ‘the Valamar is sold out this evening. This gentleman needs a room. Only for tonight. Perhaps you can accommodate.’ Naturally I declined. However my wife, speaking from her comatose oblivion, insisted we invite the stranger in. ‘Sshh, it’s fine,’ she said simultaneously snoring, ‘for today, we go to Montenegro.’

What my dream-world wife didn’t anticipate—but I did—was that our uninvited, nocturnal guest would soon become an unpleasant somnambulant nuisance and ultimately transform into a weapon-wielding demon. By the time I finally, politely asked him to depart our quarters, the intruder had morphed into a loud, apocalyptic earthquake. I awoke in a heap of sweat to a thunderous lightning storm, crawled from bed, pulled closed the trembling illuminated curtains—and swore off rakija for the balance of our Balkan holiday. I tossed and turned the rest of that uncomfortable night, occasionally glancing irritably at my happily reposed spouse. The alarm tolled at 6:15am.

In a post-hallucinogenic stupor I stumbled into the hotel lobby and ran smack dab into the selfsame night-watchman who, in my torpor, had invited Armageddon-man into our room at witching hour. ‘And you call yourselves a 5-star hotel,’ I remarked testily. He regarded me uncertainly, shrugged and opened the lobby doors. Outside, standing curbside beside a dark blue Mercedes van, stood a veritable giant of a man; our driver for the day. He grinned grimly, swung the passenger door open and commanded us to climb in. I was fearful the nightmare was continuing. But as we pulled away from the dewy curb our mountainous chauffeur politely introduced himself as Zoran and began a casual, intriguing introduction to the history of Montenegro.

The downpour began in earnest as we neared the border. The Croatian exit authority inspected our papers with palpable disinterest—then stood up, exited his cramped cubicle and promptly disappeared into the mist. ‘Between shifts,’ explained Zoran with a resigned shrug. After a 10-minute, stiflingly humid delay, an equally apathetic replacement arrived to re-scrutinize our passports. Documents eventually back in hand, we were permitted to depart Croatia and make the short descent into neighbouring Montenegro where another listless guard repeated the same agonizing process.

Everyone loves passport stamps. I entreated Zoran to ask the guard for some evidence that we were actually entering mysterious Montenegro, bragging rights for the folks back home. ‘This not good idea,’ said Zoran apologetically—but unequivocally—and we pulled away from the tiny damp station and into a strengthening deluge. It was a half-hearted, bureaucratic, blustery beginning to a soppy day. (For no discernable reason, other than inane custom and mutual distrust, countries of the former Yugoslavia demand perusal of papers upon both ingress and egress. But I digress.)

Montenegro. The name evokes visions of a small, opulent seaside protectorate where luxury yachts bob in an idyllic harbor surrounded by spectacular mountains. But while the country is indeed small, and is on the ocean, and does have a stunning mountain backdrop, Montenegro is certainly not well off. In fact Montenegro is one of Croatia’s poorest Balkan cousins. Together with Bosnia, Serbia and a few other newly-formed states, they were all part of Yugoslavia. In 1984 Yugoslavia hosted the Winter Olympics, welcoming the world’s best athletes to a snowy paradise. Nine years later the entire federation would descend into anarchy and civil war, the lid of a centuries-old pot, boiling with religious and ethnic hatred, finally blown off.

Our destination was the walled city of Kotor, a Renaissance-era gem of narrow, picture-postcard lanes. As the European crow flies, the town is not far from the Croatian border, but getting there entails a long circuitous drive around the Gulf of Kotor, which perforates deeply, fjord-like, into the Montenegrin coastline. On arrival, we exited hesitantly from the van, unfurled our umbrellas and splashed into town. What should have been an interesting, leisurely stroll down blind alleys and through colourful curio shops turned into a quick excursion—hurdling overflowing gutters and dodging the deluge spilling from dilapidated gargoyles in the old fortified town. Overall, the morning was a wet bust. Zoran was apologetic, as if he were personally responsible for the obscuring rain. ‘I wish you could see our beautiful mountains.’

But then came lunch—and, nonpareil, the best meal of our three-week Balkan adventure. I stepped, glasses fogged, into the Konoba Akustik Restaurant and discarded my broken umbrella amongst a stack of equally derelict parasols. Rainwater, dripping from the ceiling, clanged into an ancient metal pail in the foyer. Expectations were low as we dodged around the overflowing bucket and took our squeaky seats at a rustic wooden table.

Then the food began to appear. First a hearty veal soup served with fresh jecmeni—barley flatbread. Then a platter of green olives and prosciutto. Then gnocchi and pasticada—beef marinated in wine vinegar. More jecmeni arrived to sop up stray sauces. The dishes kept coming. Stuffed to the gills, I declined desert, sat back in my rickety chair, and focused my attention on the adjoining table where Zoran and two large companions sat, surrounded by three nonplussed waiters and a gesticulating chef. In unwavering concentration, they methodically devoured every dish we’d been offered plus massive plates of crni rizot—black risotto, and ajvar—spicy red pepper paste. Between mouthfuls they’d wedge in a large portion of Pag cheese. When the skewers of lamb kebab arrived I could watch no more and directed my attention to the restaurant’s ornate opaque windows and the passersby sloshing outside.

Montenegrins are not the tallest people on earth—the Dutch stubbornly cling to that lofty position. But I can state (anecdotally at least, having spent one full day in the country) that the people of Montenegro are really, really tall. And apparently it takes a lot of calories to develop that degree of vertical span.

It was a full day. On the long drizzly drive back to the Valamar Hotel, the windshield wipers flapped incessantly, hypnotizing me into a sleepy daze, interrupted only by Zoran’s occasional, meaningful collision with a muddy pothole. Nearly home, we passed through the beautiful old city of Dubrovnik. At a bus stop, under a portico tucked into the ancient city wall, I spied a small tidy man huddled under an umbrella, expensive luggage stacked neatly by his side. The fellow from my nightmare. I wiped my eyes and peered again. He was gone.

I slept dreamlessly that night.

Garth Olson says

Hi Gerry and Florence,

Really enjoyed your trip to Montenegro!

Safe travels!

Simone Schumacher says

Great memories Gerry and you're so right about that lunch, it was the best!

That was a fun article to read.